In 2009, two sisters, Jeannine and Jennifer, brought an involuntary petition before a Connecticut Probate Court to have their father conserved. (An involuntary petition is a written application made to the Court on behalf of someone else who has diminished mental capacity and who needs help managing their personal affairs and/or their finances.) Jeannine sought appointment as the conservator of her father’s person so that she could make decisions regarding her father’s health and well-being. Jennifer sought appointment as the conservator of her father’s estate so that she could pay his bills. The Court granted the sisters’ petition and appointed each of them to the roles that they were seeking.

Approximately one week later, the father’s wife and the mother of the two sisters, sued the father for a dissolution of marriage (hereinafter a “divorce”). In the complaint, the wife, Gloria, alleged that her husband was incompetent. She named Jeannine and Jennifer as defendants, as conservators for her husband. Approximately one month later, the sisters on behalf of their father filed a cross complaint seeking a divorce. Some months later, Gloria filed a motion to dismiss the cross complaint, claiming that Jeannine and Jennifer could not bring a divorce action against her on behalf of their father. In their objection, the sisters claimed that a conservator does have the right to bring a divorce action on behalf of a conserved person because they were acting in his best interests. The trial court agreed with the wife and granted her motion to dismiss. Jeannine and Jennifer appealed this decision to the Connecticut Appellate Court. The issue for the Court was whether conservators of an involuntarily conserved person can seek a divorce on behalf of the conserved person.

This issue was decided by the Connecticut Appellate Court in 2011 in the case of Luster vs. Luster, 128 Conn.App. 259. The Court began its analysis by comparing a conserved person to a minor. In its analysis, the Court stated that a conserved person is similar to a minor in that they are able to pursue civil litigation only through a properly appointed representative like a conservator. The Court reasoned that children can have limitations and restrictions imposed upon them, due to their lack of judgment. Further, children – like incompetent people – do not have the legal ability to bring lawsuits in their own names but can only do so through a legal representative. In addition, the law does not deprive an incompetent person from access to the courts. Rather, the law provides that they have representatives appointed for them to ensure that their interests are protected. Finally, the Court stated that the purpose of providing for a legal representative is to make sure that the legal disability of an incompetent person will not prohibit them from being protected under the law.

The Appellate Court also looked to Connecticut General Statutes § 45a-650(k), which stated that a conserved person shall retain all rights and authority not expressly assigned to the conservator. A conserved person cannot bring a civil action in his or her name alone but must do so only by a properly appointed representative who has a duty to protect the rights of the conserved person. The Court also looked to other Connecticut cases which provided authority for conservators to bring suit on behalf of conserved people, in order to protect their interests. Ultimately, the Court determined that nothing would prohibit the sisters in this case from bringing a divorce cross complaint against their mother, on behalf of their father.

The Connecticut Appellate Court went further, however. It concluded that the sisters had a duty and responsibility to act to protect their father’s person and estate. There were allegations in that case that contained information about the possible impact of the wife’s financial actions on the husband’s circumstances and on his possible access to medical care and housing. In addition, there were allegations that included information about the harm he could have suffered if his daughters were not able to pursue a divorce on his behalf. Because they had a duty to protect their father’s interests, the Court held that Jeannine and Jennifer had the legal authority to do so.

Situations similar to the one described in this case happen more often than you think. As the Court stated in Luster, there are other cases that have dealt with the issue of the conservator’s authority to act on behalf of a conserved person. If you are a conservator you may have the legal authority – in fact, the duty – to protect a conserved person even where it may not be apparent that you have the authority to do so. If you have any questions about your responsibilities as a conservator, feel free to contact the probate attorneys at Cipparone & Zaccaro. We would be happy to advise you with respect to your duties.

March 2019

To qualify for Medicaid (or Title 19 as it is sometimes called), you must meet both the income and asset eligibility rules. This newsletter will cover the Connecticut income rules. (Visit our website for the Connecticut asset rules.)

To understand the income rules, you will need a little Medicaid background. A “Community Spouse” is the term used for a healthy spouse of a Medicaid applicant who is living in the community. The spouse applying for Medicaid is referred to as the “Institutionalized Spouse.” The income rules vary between Medicaid for a nursing home and Medicaid for home care. We will start with nursing home Medicaid.

First, the Community Spouse’s income is not counted and, thus, the Community Spouse may keep all of his or her income. The Institutionalized Spouse’s “Applied Income” is what is used for his or her medical expenses, including nursing home charges, with two exceptions: 1.) the Personal Needs Allowance of $60 per month; and 2.) the Community Spouse Allowance.

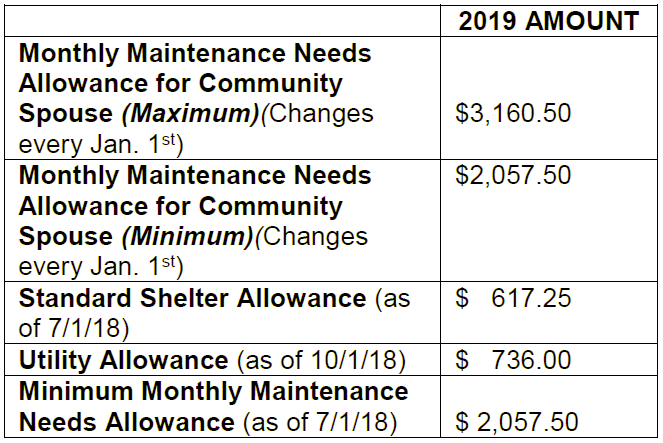

As with most things related to Medicaid, determining the Community Spouse Allowance is a complicated procedure. To begin: 1.) Total the Community Spouse’s rent, mortgage, real property taxes, condo fees and house / condo insurance; 2.) Add the standard Utility Allowance (see below for the latest allowance figures); 3.) Subtract the standard Shelter Allowance. This total gives us the monthly Excess Shelter Costs of the Community Spouse; 4.) Add the Excess Shelter Costs to the Minimum Monthly Maintenance Needs Allowance. This total cannot be higher than the Maximum Monthly Maintenance Needs Allowance; 5.) Subtract the Community Spouse’s actual income from this figure. If the result is a positive number, then this is the amount of the Community Spouse Allowance. The Community Spouse Allowance passes from the Institutionalized Spouse’s income to the Community Spouse each month. The Allowance reduces the Applied Income paid to the nursing home each month. The State of Connecticut will pay the balance of the nursing home bill.

Here is an example of how this calculation works. John is the Institutionalized Spouse and Margaret is the Community Spouse. John earns $4,000 per month income from social security and his pension. Margaret earns $1,000 per month in social security income.

Margaret’s mortgage is $1,000 per month. Her real estate taxes are $500 per month, and her homeowner’s insurance is $200 per month. With the average cost of nursing home care in Connecticut reaching $12,851 in July, 2018, John will need Medicaid coverage to afford this cost. The following is the calculation of the Community Spouse Allowance:

Because the Tentative Monthly Maintenance Needs Allowance is greater than the maximum Monthly Maintenance Needs Allowance of $3,090, Margaret’s MMNA is only $3,090. Then subtract Margaret’s monthly gross income of $1,000 and the total for her Community Spouse Allowance is $2,090.

Because John’s monthly gross income of $4,000 exceeds Margaret’s Community Spouse Allowance by $1,910, John keeps $1,910 per month. John receives his Personal Needs Allowance ($60 as of 7/1/18), pays his Medicare premium of $135.50 and the remaining amount, $1,714.50, is John’s Applied Income that he must pay each month toward his nursing home costs.

If John did not have sufficient income to pay the Community Spouse Allowance, Margaret could seek to keep more of the couple’s assets to generate the income shortfall. She would need to request a Fair Hearing and present evidence of her need to retain more of the couple’s assets to generate sufficient income.

If John were to apply for Medicaid to pay for home care instead of nursing home care, these are the calculations: The home care income limit for Medicaid under the Connecticut Home Care Program for Elders (changes every January 1st) is only $2,313 per month in 2019. John’s income exceeds the cap. Consequently, John would not qualify for Medicaid under the Home Care Program unless he diverts the $1,687 of excess income to a Pooled Trust. For more details on Pooled Trusts, see our blog What is a First-Party Special Needs Trust?

John could also apply for the state-funded Connecticut Home Care Program for Elders. The state-funded home care program provides the same services as the Medicaid home care program, but it requires the applicant to pay 9% of the cost of the care and has cost caps. The asset limit in 2019 is $37,926 for a single person and $50,568 for a couple. There are no income limits for the state-funded program. The maximum amount the state-funded program will pay for Category 2 (3 or more critical needs) is $2,909 per month; or, for Category 5 (1 or 2 critical needs) no more than 14 hours per week for a personal care attendant or 6 hours per week for a homemaker. The applicant pays the amount that exceeds the cap. Only access agencies that contract with the Connecticut Dept. of Social Services can provide the services. A care manager from the access agency will determine the level of care.

For more information regarding whether you or a loved one qualify for Medicaid or state-funded programs, contact the elder law attorneys at Cipparone & Zaccaro, P.C. to discuss your situation.